Along with many other friends, readers, and former students of his, I felt that something large and defining had gone from my life when Steve Orlen died last November—the expansive steadiness of his friendship and love, the street-level generosity of his insights into what makes us most human, our appetites and pleasures as much as our disappointments and hurts. In a profession noted for its occupational narcissism, I don’t think I’ve ever met a poet quite as curious about other people as Steve. If he was capable of wildly inappropriate questions in conversation (and he was, famously so), then one welcomed answering him because of the openness he projected.

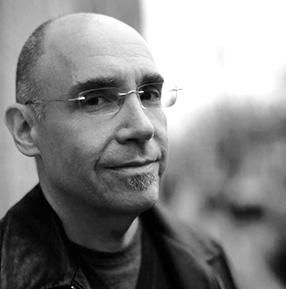

In conversation, Steve liked to tilt his head toward you, to get closer to yours. It was a gesture of intimacy and confidentiality, and not invasive. You felt it as part of his attentiveness. I met him first in 1980 as his student at the University of Arizona, when I was 26 and he was 38. He came over as a cross between an intellectual flaneur and a hood, really—there was his impressive hank of hair, yes, and the tattoo of a swallow on his forearm, the way he had of strolling rather than walking. The kind of light acne-scarring that makes some guys look “rugged.” Though straight out of mill town Massachusetts, Steve was like a character from an early Truffaut movie, a cousin of Antoine Doinel, a sensitive bad boy grown up out of the districts of the working class and set mischievously and introspectively loose upon the world. As sweet-tempered and large-hearted as he was, he had a toughness too—as a friend said after his death, he was no pussy (even if his nickname was Dr. Softy).

The toughness and generosity of spirit combined in his work to make him a poet of psychological and moral implication. Steve’s poems are alive with an urgency to speak, even when they are at their most calmly authoritative in terms of narration. People talk often about the Jarellian aspects of Steve’s work, but to me there’s more of Levine’s influence in it, and some of Lowell’s. Maybe the Lowell-influence is absorbed into such a different character that it isn’t noticeable at all (or maybe Lowell is so unfashionable now that few people would recognize it). In any case, the subtle urgency of an Orlen poem is unique—unlike some better-known narrativists of the moment, he never mistakes an engineered hysteria for drama. There is no melodrama in the work. And it should go without saying, but the narrator of Steve’s poems is compelled not only by a psychological need to tell, but also by a desire to entertain (now there’s a notion that we might want to see come back into vogue: that a poem should work hard to get you to think and feel by way of amusing and interesting material and means).

These attributes also made him one of the finest teachers of creative writing in the last fifty years. Steve was a great example of a hands-on teacher, one whose interest in craft and technique was equaled by his awareness of the moral and spiritual aspects of poetry. His judgment could be considered and tactful, generous in praise, but it was always assertive in its attentions. At Arizona and in the Warren Wilson MFA program and at Breadloaf, he was a sought-after teacher; and over the years his other students included Tony Hoagland, David Wojahn, Adrian Blevins, Michael Collier, Aga Shahid Ali, Richard Siken, Bruce Cohen, and many other well-known poets.

His primary lesson was that you had to remain a student if you expected to grow as a poet. Steve made it clear that poetry couldn’t depend simply on sensibility or character (despite the fact that his own poems had such a clear sense of personality and voice). You could acquire a syllable-by-syllable discipline by patiently picking through great poems, and you could bring it to bear on your own work. You had to.

And of course, with Steve, there was plenty of the kind of talk about poetry that crosses over into gossip (was there a bigger gossip in American poetry?). Not malicious gossip, but the kind of gossip that came out of your being a writer, a sympathetic byproduct of actually looking at the world, and observing how you moved through it with other people.

The affection and openness with which he lived all came back to Steve at the end of his life, in those three weeks after his diagnosis with cancer. His family, friends and former students came from all over to visit with him; there were long phone calls from many others. His wife, Gail, and his son, Cozi, made a generous space for all of us in that difficult moment. It was a gift to be able to be there with him in the backyard of his home, under the ramada, during some of those preternaturally beautiful days of late Fall in Tucson. The gift was something he gave—there wasn’t an ounce of self-pity in his full-on acceptance of his death, only the curiosity and large-heartedness that were so much a part of who he was.