Margaret says it’s nothing more than perspective.

She’s right, of course: perspective

being “the art of delineating solid objects

upon a plane surface so as to produce

the same impression of relative positions

and magnitudes, or of distance, as the actual objects

do when viewed from a particular point”

(Oxford Standard), the point

being the full and light-filled moon looked at,

here in mid-October, from the perspective of walking away from it

down Beacon Court. Perspective was what I lacked

an ability with when I was an art student

trying to sight down the row of different-storied

buildings on the far side of the street,

each one distinct yet connected,

as in a Hopper or Utrillo,

sun shadow or pencil-marking rain. Night, though,

is another thing altogether.

I’d just turned to consider

the blue cloud passing like a floating island nation

on the opposite end of the sky, then

turned back only to realize how high the moon had traveled,

had, in no time, risen as if lifted.

Perspective, Margaret said: like the problem I had drawing

depth of field, the illusion of a line diminishing

(the famous looming stones of graves in Queens

foreshadowing the skyline of Manhattan),

since perspective is as much about

the imagination as it is about

Brunelleschi.

As memory,

too, like too much in our lives, is perspective,

and between now and then often all we have.

Those, for instance, whom we’ve loved and unloved,

forming a line behind us, eventually fade,

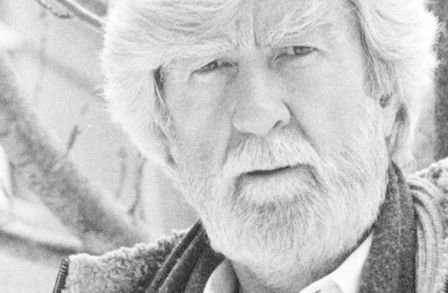

in the long century photograph,

to the size of children or the half

of half of nothing of what they were.

I don’t have the answer.

Come close, we say, but keep your distance

(as if perspective were a dance).

And as you walk away you’ll disappear

(as if you’d not existed, were never here).